15 Workshop 2

Week 5

15.1 Part 1 - Preliminary questions

Formative (i.e., not assessed), for practice, and does not need to be submitted

15.1.1 Work done in circular motion

What is the rate at which work is done on a particle executing motion in a circle at a constant speed?

Resultant work done during circular motion at uniform speed is zero, since the force is acting perpendicular to the direction of motion and so \(\vec{F} \cdot \vec{dr} = 0\).

15.1.2 Neutron colliding with carbon nucleus

A neutron of mass \(m_n\) and speed \(v_{ni}\) undergoes a head-on, perfectly elastic collision with a carbon nucleus of mass \(m_C\) initially at rest. You may assume Newtonian mechanics applies.

- What are the final velocities of the neutron and carbon nucleus?

- What fraction of its initial energy does the neutron lose?

The question specifies a head-on collision. This implies that the recoil velocities, after the collision, will be along the same line as the initial velocity. So we are dealing with a one dimensional elastic collision here. Conservation of momentum and conservation of energy can both be applied. (Conservation of energy because the collision is elastic).

A carbon nucleus is (to a good approximation, assuming the most common isotope of carbon) 12 times more massive that a neutron so we expect the neutron to “bounce back” with close to its initial speed while the carbon nucleus moves away rather more slowly in the original direction.

So, taking \(v_C\) in the original direction and \(v_{nf}\) in the opposite direction, we have from conservation of momentum, \[ m_n v_{ni} = m_C v_{Cf} - m_n v_{nf}. \tag{15.1}\]

Conservation of energy gives \[ \frac{1}{2} m_n v_{ni}^2 = \frac{1}{2} m_C v_{Cf}^2 + \frac{1}{2} m_n v_{nf}^2. \tag{15.2}\] We solve these two equations for \(v_{Cf}\) and \(v_{nf}\). There are different ways you can do this, including the following. Rearranging and squaring Equation 15.1 gives \[ m_C^2 v_{Cf}^2 = (m_n v_{ni} + m_n v_{nf})^2. \] We can get another expression for \(m_C^2 v_{Cf}^2\) from Equation 15.2, \[ m_C^2 v_{Cf}^2 = m_C ( m_n v_{ni}^2 - m_n v_{nf}^2 ). \] Equating these, we get \[ m_n^2 (v_{ni} + v_{nf})^2 = m_C m_n (v_{ni}^2 - v_{nf}^2) \] \[ m_n (v_{ni} + v_{nf}) = m_C (v_{ni} - v_{nf}) \] \[ v_{ni} (m_C - m_n) = v_{nf} (m_n + m_C) \] \[ v_{nf} = \frac{m_C - m_n}{m_C + m_n} v_{ni}\] \[ v_{nf} = \frac{11}{13} v_{ni}\]

And then, from Equation 15.1, \[ v_{Cf} = \frac{m_n v_{ni}}{m_C} \left( 1 + \frac{11}{13} \right) = \frac{24 m_n v_{ni}}{13 m_C} \] \[ v_{Cf} = \frac{2}{13} v_{ni} \] assuming the ratio of the particle masses is exactly 12. These values confirm our initial expectations since \(v_{nf}\) is close to \(v_{ni}\) and the carbon nucleus speed is considerably smaller.

The fraction of kinetic energy lost by the neutron is \[ \frac{ \frac{1}{2} m_n v_{ni}^2 - \frac{1}{2} m_n v_{nf}^2 }{ \frac{1}{2} m_n v_{ni}^2 } \] \[ = \frac{1 - \left( \frac{11}{13} \right)^2}{1} = \frac{48}{169} = 28\% \]

15.1.3 Vector products

Find the vector product \(\vec{a} \times \vec{b}\) of the following vectors.

- \(\vec{a} = 4 \hat{\imath}\) and \(\vec{b} = 6 \hat{\imath} + 6\hat{\jmath}\).

- \(\vec{a} = 2 \hat{\imath} + 3 \hat{\jmath} − \hat{k}\) and \(\vec{b} = 3\hat{\imath} + \hat{\jmath} + 4\hat{k}\).

If you haven’t seen the vector product before, we will go through this in lectures. You can find out more by looking at Section 8.1 of the notes. Here is the information you need to answer this question.

The vector product of two vectors \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\) produces a third vector \(\vec{c}\) that is perpendicular to both \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\). The magnitude of \(\vec{c}\) is equal to the area of the parallelogram formed by \(\vec{a}\) and \(\vec{b}\).

There are various ways to calculate \(\vec{c}\) including the determinant method described below.

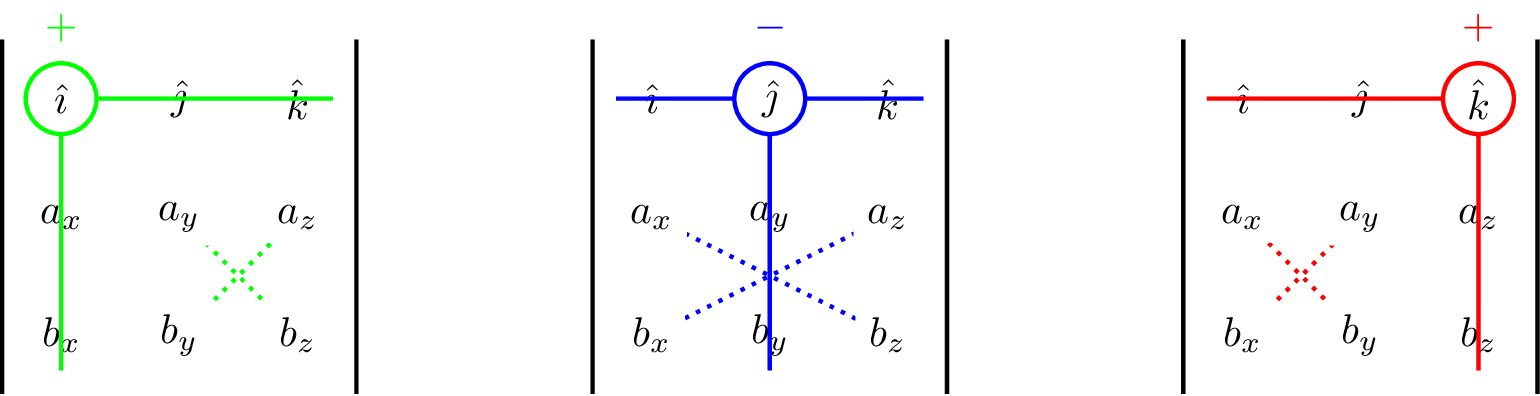

\[ \vec{c} = \vec{a} \times \vec{b} = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\imath} & \hat{\jmath} & \hat{k} \\ a_x & a_y & a_z \\ b_x & b_y & b_z \end{vmatrix} \]

\[ \vec{a} \times \vec{b} = {\color{green} +(a_y b_z - b_y a_z) \hat{\imath}} {\color{blue} -(a_x b_z - b_x a_z) \hat{\jmath}} {\color{red} +(a_x b_y - b_x a_y) \hat{k}} \]

Note the “\(-\)” sign associated with the \(\hat{\jmath}\) term.

You can either remember the pattern we look at in lectures, or do the cross product term-by-term. We’ll write it down term-by-term here

\[ 4\hat{\imath} \times (6\hat{\imath} + 6\hat{\jmath}) = 4 \hat{\imath} \times 6\hat{\imath} + 4 \hat{\imath} \times 6\hat{\jmath} \] because the vector product is distributive.

\[ \hat{\imath} \times \hat{\imath} = \vec{0} \] \[ \hat{\imath} \times \hat{\jmath} = \hat{k} \] Which gives the final answer \[ \vec{a} \times \vec{b} = 24 \hat{k} \]

This is probably easiest to do using the determinant method (if you’re familiar with that) or the pattern / formula we looked at in lectures. However, to be clear, we’ll write it down term-by-term as this makes it clear what we are doing. Remember that the cross product is distributive. \[ (2 \hat{\imath} + 3 \hat{\jmath} − \hat{k}) \times (3\hat{\imath} + \hat{\jmath} + 4\hat{k}) \] \[ = 2 \hat{\imath} \times \hat{\jmath} + 2 \hat{\imath} \times 4\hat{k} + 3 \hat{\jmath} \times 3\hat{\imath} + 3 \hat{\jmath} \times 4\hat{k} - \hat{k} \times 3\hat{\imath} - \hat{k} \times \hat{\jmath} \] where we have removed the \(\hat{i} \times \hat{i}\), \(\hat{j} \times \hat{j}\) and \(\hat{k} \times \hat{k}\) terms because they are zero. We can then look at the cross product of the basis vectors individually remembering that the cross product produces a right-handed set of vectors. \[ \vec{a} \times \vec{b} = 2\hat{k} - 8\hat{\jmath} -9 \hat{k} + 12\hat{\imath} - 3\hat{\jmath} + \hat{\imath} \] \[ = 13 \hat{\imath} - 11 \hat{\jmath} - 7 \hat{k} \]

15.1.4 Person pulling sled

A girl pulls a sled in which her brother sits, over the snow. She pulls a rope over her shoulder which is attached to the sled. The boy has mass 19 kg, the sled has mass 1.4 kg, the girl is 1.2 m high at the shoulder and the rope is 2.4 m long. You may assume that the coefficient of kinetic friction \(\mu k\) between the sled and the snow is 0.1.

- Draw a diagram of the forces acting on the sled, assuming it travels at a constant speed. What are the forces acting on the girl?

- What is the tension in the rope?

- The girl changes the position she is carrying the rope, dragging the rope now at a height of 0.6 m. Does she have to increase or decrease the force with which she pulls on the rope to maintain a constant speed?

- The girl is now pulling the sled over grass for which \(\mu_k = 0.5\). Plot a graph of the tension versus the angle between the rope and the ground, and explain what you see.

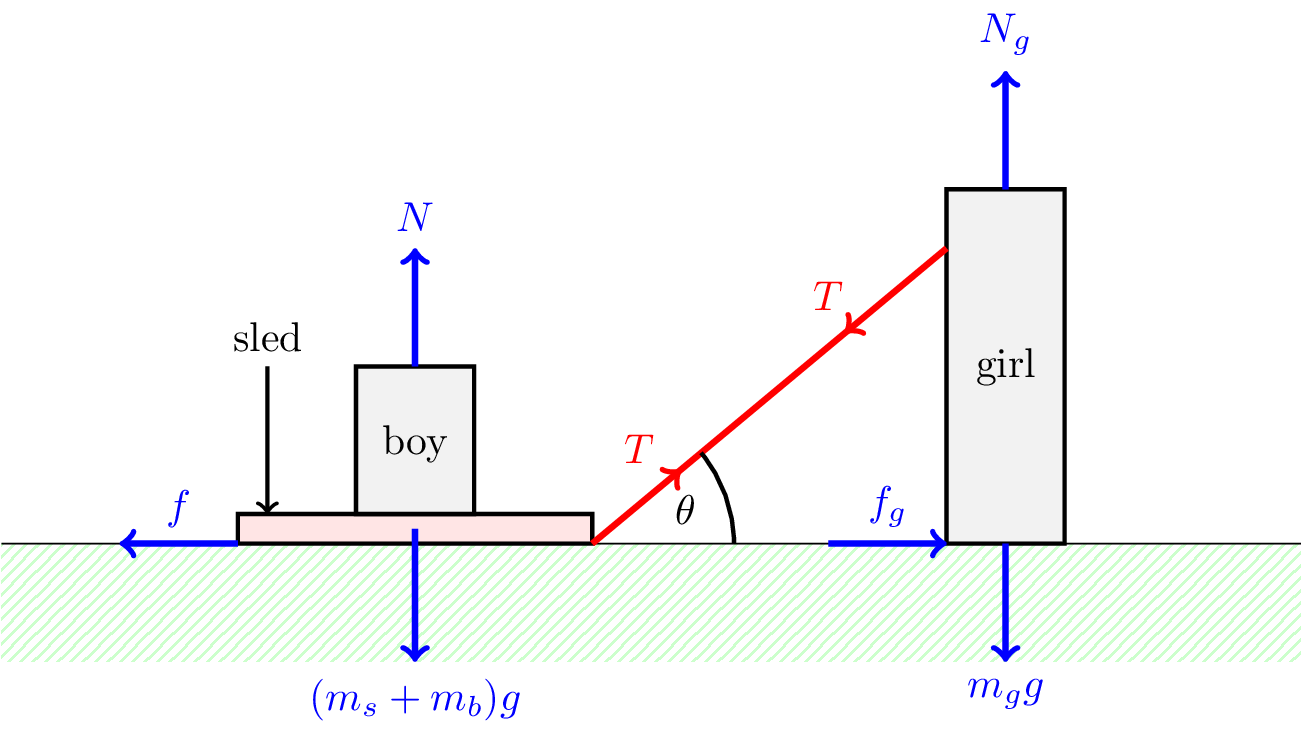

The forces are shown in Figure 15.1.

The sled is acted on by

- the tension \(T\) in the rope at \(\theta = 30^\circ\) to the horizontal (assuming the sled is at negligible height, as the rope is twice as long

- kinetic friction \(f\) acting backwards horizontal,

- the weight of the sled and the weight of the boy, \((m_s + m_b)g\), acting downwards, and

- a normal reaction \(N\) upwards.

Since the sled moves at constant velocity, the sum of these forces should be zero.

The girl is acted on by:

- the tension in the rope, \(T\) (at \(-30^\circ\) to the horizontal),

- her weight \(m_gg\) downwards,

- a normal force \(N_g\) upwards and

- a forwards static friction force, \(f_g\).

These should cancel out because there is no net acceleration.

The forces balance, so taking components for the sled, we have the following. Horizontally, \[ T \cos \theta = f = N \mu_k \tag{15.3}\] and vertically, \[ T \sin \theta + N = (m_s + m_b)g \tag{15.4}\] where the angle \(\theta = 30^\circ\). We can substitute \(N = T\mu_k^{-1}\) from Equation 15.3 in Equation 15.4 and rearrange to get \[ T = \frac{(m_s+m_b)g}{\sin \theta + \mu_k^{-1} \cos \theta} \] Substituting in the numbers gives \[ T = 21.9 \text{ N} \]

If the new angle of the rope is \(\theta'\), we now have \(\sin\theta' = 1/4\) and \(\cos \theta' = \sqrt{15}/4\). Since, in the denominator of the equation we found in the previous part, \[ \frac{1}{4} + 10 \frac{\sqrt{15}}{4} = 9.9 > 9.2 = \frac{1}{2} + 10 \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \] The new tension is smaller than the previous tension. Physically, this can be explained because at the shallower angle more of the tension contributes to the horizontal component, balancing the friction; this has a greater effect than the increase in friction due to the increased normal force.

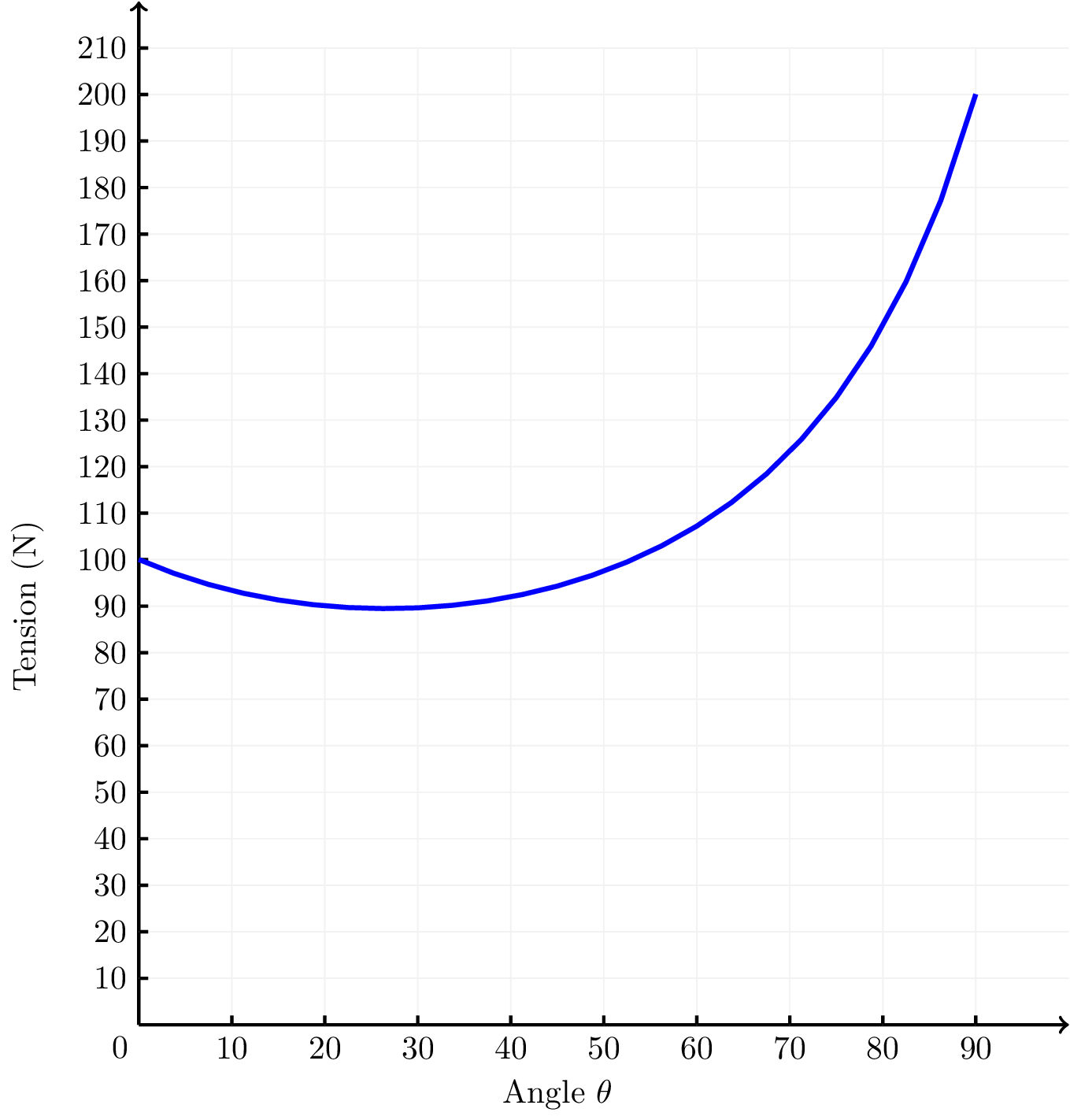

The tension initially decreases when we start to increase \(\theta\), as there is more benefit from increasing the component of \(T\) that is lifting the sledge and reducing the friction. As \(\theta\) continues to increase, \(T\) then increases for the reason given in part (c) - we start paying the price for reducing the forward component of the tension and have to pull harder. This is shown in Figure 15.2.

15.2 Part 2 - Problem solving question

Summative (i.e., counts 3.75% towards final grade), please submit PDF individually

The problem solving question will be provided during the workshop session.